If you have been to the colonial Jewish synagogues in Curaçao, Barbados, or

Suriname, or the (Old or New) Jewish Cemeteries in Curaçao, you will begin no notice recognize an interesting pattern: black and white tiles arranged in checkerboard fashion surrounding entrances to buildings and around the base of gravestones. This pattern can also be seen in the nineteenth-century Jewish houses in the

Scharloo district of Curaçao. It is often referred to by the name "mosaic pavement."

(Mosaic Pavement outside Neve Shalom Synagogue in Paramaribo, Suriname at Left.)

|

| Mosaic Pavement in the Newer Jewish Cemetery in Curaçao |

If you are a

freemason, the pattern will seem doubly familiar. Mosaic pavement was (and is) a staple of both Masonic

architecture and ritual objects. Masonic carpets and later floorings employed

the mosaic pavement motif. used

the pavement in the center of their sanctuaries either in tile or on a rug, usually surrounded by a border and with the symbol of

a blazing star at the center. Although Masons were not the only people to use this type

of flooring during this era, mosaic pavement took on special resonance within

Masonic rites and are usually noted in emblem charts (like the one below) and were often used in Masonic lodges during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

|

| Emblematic chart and Masonic history of F[ree] and A[ccepted] M[asons]

/

Ramsey, Millet, & Hudson Steam. Lith. Co. (Kansas City, Mo. : W.M. Devore, publisher, c1877). Courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-DIG-pga-02426 |

Masons--like early American Jews--were interested in mosaic pavements for a reason. Neo-classical marble checkerboard floorings reflected a general

interest in antiquity, but they were also explicitly associated with Solomon’s

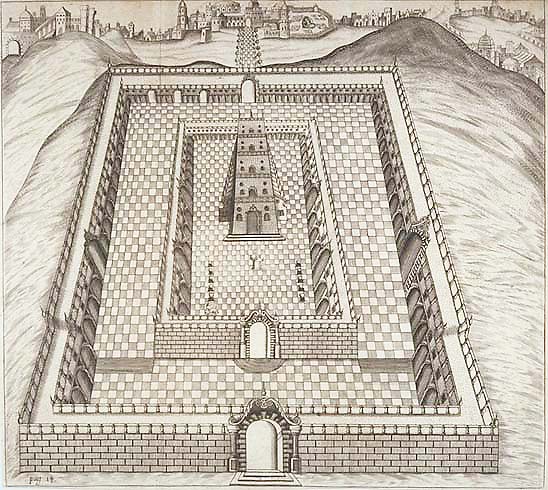

Temple throughout the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. While Amsterdam Rabbi Leon de Templo

depicts the interior courtyard of the Temple Mount in his model as paved in uniform square

tiles, other scholars of the Temple explicitly used the checkerboard motif for

the Temple’s courtyard, such as Samuel Lee in the diagram to the left. By at least 1730, mosaic pavement design (often

in the form of a floor cloth) was a mainstay of Masonic Temples

because of the

pavement’s Solomonic association. When early Masons met in coffee shops, they

decorated the meeting spaces with Temple motifs.

Indeed, until the nineteenth century when lodges

expanded their membership and more routinely acquired property, lodges used

portable symbols, badges and signs to signal connections to Solomon’s Temple

and set an appropriate mood for meetings. Other important Temple symbols used in masonic rites included the

Ark of the Covenant and the pillars of

Jachin and Boaz (the two pillars in the emblem chart above).

Even the apron worn by masons (such as George Washington below) has been read as related to

ephod (apron) of the sacred garments of the Kohen Gadol, shown below on the left of the frontispiece of the Amsterdam Haggadah of 1695.

|

| George Washington in Masonic Regalia, including the Masonic Apron. "Washington as a freemason," (

c1867). Courtesy of the Library of Congress,

LC-DIG-pga-04176 |

To learn more about connections between Jews and Masons, see my earlier post on

Masonic Jews and my chapter on "The Secret Lives of Men" in

Messianism, Secrecy, & Mysticism: A New Interpretation of Early American Jewish Life (2012). In my book, I talk about some of the key differences between the Jewish and Masonic uses of mosaic pavement, and the reasons why freemasonry was popular among early American Jews.