I have been thinking lately about

Rabbi's houses in colonial America, in part because I will be speaking about early American Jewish houses at the

AJS (Association for Jewish Studies) Conference

in December, and in part because I have been transcribing a section of

the minute books of Congregation Nidhe Israel in Barbados in which the

Rabbi, his house, and his household keep getting mentioned. Today the

historical Rabbi's house in

Curaçao is a tranquil oasis, but apparently during the colonial era the houses were vibrant places to visit or live.

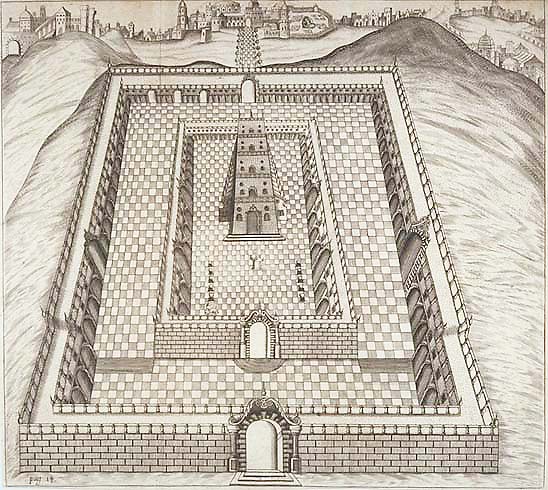

In

Curaçao, like in

Barbados,

Suriname, and Amsterdam, the Rabbi's house was part of the synagogue complex that also included a

mikveh (

ritual bath), school space, and the synagogue itself,

called the “

Snoa” in Curaçao and

Esnoga in Amsterdam (

Ladino:

אסנוגה). Although the house in Barbados has been destroyed, the Rabbi's house in

Curaçao is still standing and is beautifully maintained as part of the exquisite

Jewish Historical Museum.

|

| Panorama of the Rabbi's House on Kuiperstraat (Stevan J. Arnold, ©2012) |

|

| Detail (Stevan J. Arnold, ©2012) |

|

|

|

The Rabbi’s House was

built in 1728 at 26-28 Kuiperstraat, in the heart of the older

Punda neighborhood. Although it became part of the a group of buildings that now form the synagogue complex, the house predated the

placement of the synagogue: as the Jewish population on the island flourished,

the congregation outgrew its initial space and moved in successively in

1671-75, 1681, 1690, 1703. In 1729 the fifth synagogue was destroyed in order

to build the sixth (and final synagogue) adjacent to the Rabbi’s home.

Although early on a house was adapted to meet

the congregation’s needs, both in 1703 and 1732, the community built a

structure explicitly as a synagogue. The current house was likewise an

extension of a predecessor. In 1704 the Mahamad (Board of directors or council of elders of a Spanish-Portuguese Synagogue) bought a larger house for

Rabbi Eliau (Elijah) Lopez and his successors. This house was “revised” in 1728, the

date it now bears (Emmanuel & Emmanuel,

History,

51, 87-88, 93-95, 120-24, 143, 1163).

Unlike

Merchant houses, which often housed offices or goods for sale and were located

near the wharf, the “business” of the Rabbi’s house was primarily ritual and

liturgical. By the 1730s the Snoa had to compete with a second synagogue and Jewish school in

Otrobanda, though the Snoa complex still laid claim to being the house of the Island's Rabbi.

|

| Panorama of the Rabbi's House (Photo by Stevan J. Arnold, ©2012) |

Architecturally the house shares many features with its neighbors, including the graceful balconies (shown above and below) that were so popular in the Punda neighborhood during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that helped keep residents cooler.

Like Amsterdam’s

canal houses, older houses in Curaçao were usually built with brick. Unlike in

Amsterdam, however, where the brick was left exposed, in Curaçao the brick was

typically covered in plaster or stucco (Winkel-151-55).The plaster was then whitewashed or painted

in a “bright bold palette” not favored in the Netherlands. Allegedly houses began to be painted because

an early governor found the white-washed buildings “fatiguing to the eye” due

to the way the reflected the tropical sunlight.

|

| Balcony of the Rabbi's House (Photo Stevan J. Arnold, ©2012) |

To visit this lovely historical house, pay the small entrance fee and enter through the main gates of the

Snoa.

- http://www.curacaomonuments.org

- Emmanuel, Isaac S. and Emmanuel,

Suzanne A., History of the Jews of the

Netherlands Antilles (Cincinnati, OH: AJA, 1970).

- Winkel, Pauline Pruneti, Scharloo: A Nineteenth Century Quarter of

Willemstad, Curaçao: Historical Architecture and its Background (Florence:

Edizioni Poligrafico Fiorentino, 1987).